- Introduction

- The Medium is the Message

- Ed Tech: The Same Old Same Old

- Generative AI as a Hot/Cool Hybrid Medium

- The Pros of Educative AI

- The Cons of Educative AI

- Process over Product

- AI and the Liberal Arts

Introduction

A decade ago, as a graduate student at Columbia, I became deeply interested in the concept of digital workflows for academic researchers, something that has continued to engage me. In an educational landscape undergoing a profound transformation, technology has shifted from being an intriguing novelty to an essential element of teaching and learning. It’s therefore critical that we reassess our approaches to how we use this technology. The initial widespread enthusiasm for educational technology, which has grown into a multi-billion-dollar industry, has faded as it became ubiquitous during the COVID pandemic and problems have arisen both with smartphones and other technological distractions in schools. The effectiveness of educational technology, in the periods before and after the pandemic, is now under close scrutiny.

The 2023 UNESCO report, An Ed-Tech Tragedy? Educational Technologies and School Closures in the Time of COVID-19, offers a stark evaluation of these technologies. It suggests that not only did technology fail to live up to its high expectations, but the pivot to it during the pandemic was profoundly disappointing. The 656-page report, in “documenting the severity and scope of the many negative consequences of ed-tech responses during the health crisis inverts the triumphalist narratives that accompany many descriptions of technology deployments to address the educational disruption caused by school closures.” This sobering perspective necessitates that we carefully reassess the real impact and future possibilities of these technologies, particularly in the era of generative AI tools like ChatGPT, which have quickly become prominent in educational settings.

Despite the significant learning setbacks experienced by students in elementary, middle and high school from over-dependence on technology during the pandemic, a chorus of optimistic and influential voices is now greeting the arrival of generative AI in the classroom, some with utopian hype. The Economist asserts that “AI can transform education for the better.” Bill Gates envisions AI as something “like a great high school teacher,” while others assert it can “make teachers better” through “observational feedback.” Sal Khan, the eponymous founder of his online learning academy, famous for direct instruction lectures delivered on YouTube, makes the boldest claim yet: “We’re at the cusp of using AI for probably the biggest positive transformation that education has ever seen.”

Others offer more tempered views of AI learning technology. The Wall Street Journal notes that Khan’s own AI tutoring program, “Khanmigo,” struggles with math and tasks that require deeper understandings, and thus reveals the gap between actual performance and hopes of perfection. Another serious issue is that easy access to AI among students has resulted in an explosion of academic dishonesty, with cheating by GPT replacing former modes of cheating. Of major concern is the tendency of AI to generate false information, called “hallucinations,” and its inherent algorithmic biases, which can lack both reliable sourcing and diversity of views. Due to limited subject expertise, students can often fail to detect these flaws. Indeed, mathematician Nassim Taleb is skeptical, arguing that tools like ChatGPT are “ONLY usable if you know the subject very, very well … making embarrassing mistakes only a connoisseur can detect … So if you must know the subject, why use ChatGPT?” Taleb’s critique suggests twin imperatives for educators. Before rapidly integrating still-limited AI technologies into the classroom, educators must determine how to leverage AI guided by the best standards and practices, while applying sound pedagogical principles attuned to its unique media effects.

In this essay, I reevaluate the use of AI in education in three key ways. First, I apply Marshall McLuhan’s media theory to identify generative AI as a unique hybrid medium that synthesizes elements of both “hot” and “cool” media. Next, I argue that AI’s hybrid nature should inform how we integrate AI with the purpose of promoting participatory learning, which include the skills rooted in “hot media”— like critical reading, logical interpretation, textual analysis, and writing—and tools that integrate the interactivity of “cool media.” I contend that the responsible implementation of AI requires pedagogical approaches that intentionally nurture these essential interpretive capabilities alongside the discursive, student-centered use of AI. Finally, I examine implications for our philosophy of assessment, critiquing overreliance on product-focused evaluations in favor of transparent, process-oriented authentic assessments. I argue that AI can play a constructive role as one of other dynamic skill-building activities rooted in student collaboration and growth-oriented feedback. Ultimately, I call for the necessary return to liberal arts education as the only kind capable of preparing students holistically for the post-AI world. Amidst specialized disciplines, the liberal arts teach students enduring first principles and develop the sophisticated cognitive skills they need to use and improve upon AI advancements.

The Medium is the Message

Marshall McLuhan’s main insight that “the medium is the message” in Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964, p. 9) gives us a valuable framework for how we can think about Large Language Model-based (LLM) generative AI technologies. In a now famous formulation of this principle he says,

the medium … shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action. The content or uses of such media are as diverse as they are ineffectual in shaping the form of human association. Indeed, it is only too typical that the ‘content’ of any medium blinds us to the character of the medium.

Ed Tech: The Same Old Same Old

There is no doubt that, from the vantage point of the 1960s, the dawn of personal computer technology in the 1970s and 1980s has substantially changed our world. To make one example: it is now clear that the content of news and civic discourse, when transferred to the digital medium of the internet, social media, smartphones and 24-7 cable news cycles of the 21st century, significantly alters society’s experience of it. Computer technologies and the internet have shaped and mutated “the scale and form of human association and action” in novel ways. The internet has put previously inacessible quanta of information at our fingertips.

But the irony of the last twenty to thirty-year obsession with educational technology is how little substantial change it has made in our experience of content in schools. The fact is that the majority of educational technologies have merely digitized traditional media, such as lecture notes and documents or literary/informational texts, by moving them onto a screen and adding some degree of manipulability in the medium. They have not, however, fundamentally changed, or revolutionized, the nature of the learning process.

Platforms like Microsoft Office 365, Google Classroom, and Learning Management Systems (LMS) like Blackboard and Canvas, in effect extended traditional processes of interacting with content from the paper world onto the screen. Not to belabor the point, but a PowerPoint presentation is very much like the transparent overhead projector of forty years ago, just as file folders, PDFs, and threaded discussions resemble digitized versions of informational reading, writing, and viewing processes that would have been logical, in principle, even to Gutenberg despite the novelty of the internet and personal computer.

I first examined digital workflow and learning technologies in my 2014 essay PDF Chaos? Digital Workflow Basics – Humanities & History Blog (columbia.edu) for the Humanities & History Blog at Columbia University (the first installment is here). Although the digital environment seemingly offers an almost magical sense of participation, the underlying processes of computerized work aren’t fundamentally different from non-digital ones. I urged people to remember that “We can confuse the ‘medium’ with the ‘message’:

. . . since the whole development of the GUI (Graphical user interface) and WYSIWYG (What you see is what you get) interface back at the Xerox Parc research center, and even before that, Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad (1963)—which produced the concept behind the user interface we are so familiar with in the Microsoft Windows and Apple Macintosh operating systems—we have to remember that even leaving the whole problem of apps aside (see my previous post), the “operating system” was from the beginning entirely modeled off the banality of “files,” “folders,” and note “tags” of the analog office process of the pre-digital, “paper pushing” era. Indeed this is still a valid model for all productivity and workflow (see Merlin Mann’s 43 Folders), especially in academics. In his Laws of Media: The New Science (1992), Marshall McLuhan pointed out that the new media technology as tool forms are always an extension of our body or sensual organs. As much as a “mouse” is a bodily input device, so the folder is a digital collection bucket. In this sense, the “file,” “folder,” and “tag” … is still very much an old concept … just as you would need to have a system for naming files, filing them, categorizing them, and “tagging” them in an analog system—and depend on it consistently every single time—so you need it in its digital equivalent, without looking at the computer as something that it’s not: a semi-autonomous, automatic thing managing machine. When computer technology appears to our consciousness as a quasi-autonomous interface or interactive experience—as it often does with our proliferation of apps, devices, and “multimedia”—rather than an extension of our bodies, we easily default to the Google sirens and fall in the gadget trap. We can confuse the “medium” with the “message.” That is, we believe we don’t need to manage our files and apply extensive rational intelligence to it as we would in the paper world. The ability to “Google” or “Spotlight Search” documents creates an illusion or simulacrum of a system, but it is only an operating system, that is an apparatus of files, folders, etc., in which a user must use it intelligently and rationally, deploying its tools and structure in regards to process and product. We need to have a process and deliberate collection system.

Today’s LLM Generative AI departs from the above paradigm, in which digital tools and applications only seemingly automated information management yet required users to engage in essentially manual, “hot media” processes which organized the paper world on a screen. Unlike the superficial digitization of the past, where the essence of organizing and interacting with information remained unchanged, today’s AI introduces a genuinely automated, interactive, and highly-participatory dimension to learning and knowledge management. We are tempted to call it an artificial brain, but it is just a probabilistic algorithm that feels like a brain. AI gives us not merely the paper world transposed onto a screen; instead, it’s a leap into a realm where the technology itself automates and then channels reciprocal participation in the educational process: guiding, questioning, and customizing information and the learning experience in real time. The contrast with the digital situation I analyzed in 2014 is stark. Where once users had to manually impose order on digital chaos, AI proposes to navigate, interpret, and even curate the informational deluge for us. It seems to embody a true shift from manual organization in the digital realm to automated cognitive engagement, but as such, the form of engagement with content through the AI medium remains a puzzling chimera.

Generative AI as a Hot/Cool Hybrid

To help us think about what sort of media experience AI actually is, McLuhan’s distinction between “hot” and “cool” is crucial. He writes:

Any hot medium allows of less participation than a cool one, as a lecture makes for less participation than a seminar, and a book for less than dialogue. With print many earlier forms were excluded from life and art, and many were given strange new intensity. But our own time is crowded with examples of the principle that the hot form excludes, and the cool one includes (1964, p. 25).

McLuhan divides media into “hot” and “cool” based on the level of audience participation required. Hot media, including printed materials like textbooks and photographs, as well as radio and feature films, deliver information in a high-definition, detailed manner, directly targeting a specific sensory experience. This mode of delivery promotes a direct, linear approach to thinking and learning, encouraging the user to absorb information in a segmented and specialized way. Despite requiring the audience’s full attention due to their content-rich nature, hot media do not demand significant interaction from the viewer or reader. For instance, when students engage with primary sources, by reading through a textbook or completing a graphic organizer, they are fully immersed in a detailed and comprehensive learning experience. However, this type of engagement is characterized by low participation because the media provides all the necessary information directly, leaving little room for the audience to contribute or interact with the content beyond absorbing it.

In contrast, cool media, such as episodic television (especially news commentary, animations, game shows, and reality television), spoken conversations, and the use of telephones, offer less detailed content, requiring the audience to play a more active role in interpreting and engaging with the media. This category includes social media platforms, which, despite their rich mix of images, videos, and texts, foster a more interactive and participatory experience compared to reading a novel, studying from a textbook, or attending a traditional lecture. Cool media requires the audience to fill in more gaps, making their participation crucial for a complete engagement with the content.

Hot media, in general, do most of the work in our receiving information. Reading textbooks and conventional writing tasks are considered hot because they directly provide comprehensive and detailed information to the audience. The hot mode of information delivery engages the audience’s cognitive faculties fully but passively, by understanding and absorbing materials. Hot media doesn’t require and seldom allows for interactive engagement or personal input beyond the processing of the provided information. In essence, hot media denotes minimal involvement and contribution of the audience in the creation, interpretation, or discussion of content.

Cool media, in general, require that we participate more in the work of receiving information. McLuhan’s discussion of cool media—such as TV shows, movies, and in our day, videos on various social media platforms—as opposed to hot media, is particularly illuminating for educators and relevant to an accurate understanding of AI as partially cool in educational settings: “Intensity or high definition engenders specialism and fragmentation in living as in entertainment, which explains why any intense experience must be ‘forgotten,’ ‘censored,’ and reduced to a very cool state before it can be ‘learned’ or ‘assimilated’”(1964, pp. 8-9).

In education, generative AI is a hybrid of hot and cool media. As a hybrid, AI provides a rich, interactive textual content in high definition, and therefore, a very high cognitive load, but it also requires a high degree of active learner participation, for example by entering and revising prompts, an action reminiscent of low definition cool media.

When considering which academic teaching methodologies are most effective, educators must distinguish between traditional and participatory learning and how each impacts student success. It’s long been known that students with highly developed executive functions usually excel in environments rich in direct instruction with lectures, models, readings, and rote memorization assessments—a scenario reminiscent of Marshall McLuhan’s concept of hot media; this approach, however, does not benefit all learners. McLuhan’s assertion that “hot” content must be “reduced to a very cool state” to facilitate learning and assimilation, underscores the necessity of adapting educational content to a broader spectrum of learning styles. The transition from hot to cool media in education thus requires that students shift from a passive reception of information to a participatory learning process.

My theory is that generative AI, with its unique interactive capabilities, is a hybrid medium that synthesizes McLuhan’s hot and cool media. Traditional digital tools on the screen mimic the paper world and require user engagement that is essentially manual; as such they embody hot media’s characteristic of delivering detailed, high-definition content with minimal participation. In contrast, generative AI introduces an automated, interactive dimension to information management and learning. AI does not merely digitize existing information; it actively engages in the educational process by customizing and guiding the learning experience in real time. Through its capacity to navigate, interpret, and curate content, generative AI, like cool media, requires users to participate in less defined content by filling in gaps and thereby contributing to the creation and interpretation of knowledge. However, unlike pure cool media, generative AI also delivers detailed, contextually rich information and thus has attributes of hot media. The dual nature of generative AI, which combines the detailed, immersive experience of hot media with the interactive, participatory essence of cool media, makes it a hybrid medium. And as a hybrid medium it fundamentally alters the way we engage with and manage information.

Understanding generative AI as a unique hybrid medium brings me to my central question: How can we best leverage AI technology to promote optimal learning outcomes, given its dual media effects which offer both promise and peril? On the one hand, AI has tremendous potential to enhance learning through customized, interactive experiences. On the other hand, AI’s haphazard production of erroneous outputs threatens academic integrity and underscores the need for vigilance. Its perils therefore necessitate its careful integration into learning practices that are guided by core educational priorities. If we are to realize AI’s benefits while mitigating its risks, we must reframe our educational philosophy, curriculum, assessments and instructional practices to align with the participatory affordances of this technology. Below I present the pros and cons of educative AI with some comments about enhancing the former and containing the latter.

The Pros of Educative AI

- AI can simulate key activities of direct instruction by automating the repetitive practice and assessment of core concepts. Teachers can then focus instruction on the more advanced, higher-level cognitive skills and tasks of analysis and critical thinking.

- AI algorithms produce an interactive, user-focused exploration of information based on immediate input and output and thereby quickly facilitate data-rich “conversations” on a vast range of topics; these outputs include broad generalizations, detailed specifics, categorized data, patterns as well as explanations of topics and connections between and among topics.

- In the Social Studies or ELA classroom, AI can help educators and students move beyond the traditional input of printed materials, lectures, slides, or textbooks, which students absorb and then translate into outputs like notes or graphic organizers. When thoughtfully used, AI can transform traditional learning into student-centered participatory instruction. This AI model has three stages: input from both the teacher and information sources; input from the student interacting with AI (in which the teacher provides output and source input); and finally, the AI output alongside the student’s output. This complex multi-stage input-output process emphasizes student participation, making learning more interactive and dynamic. Needless to say this process demands full executive function and is cognitively taxing.

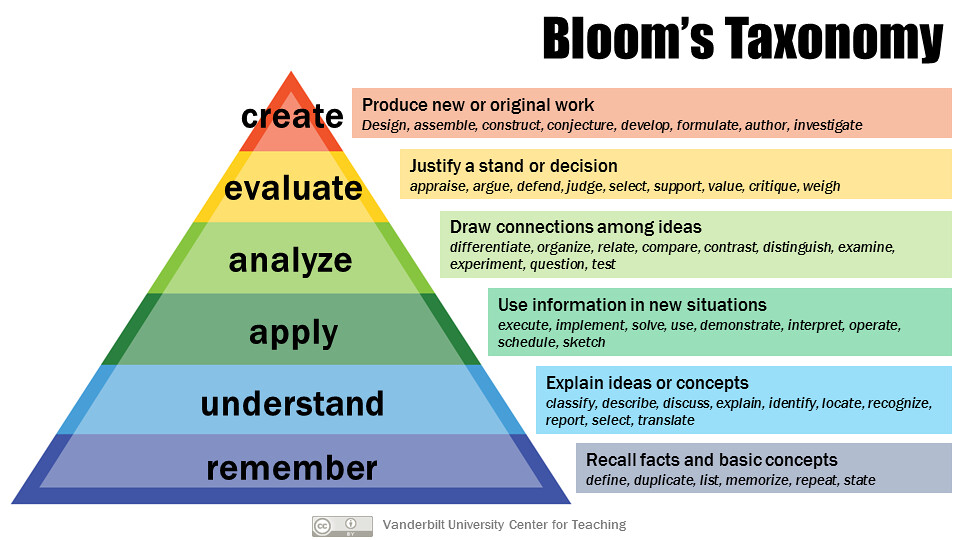

- AI is particularly helpful with student acquisition at the foundational learning level—like remembering and understanding— as outlined in the lower levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. AI tools can quiz students on memorized facts, generate examples, fill in knowledge gaps and clarify confusing concepts, and use flashcards and adaptive software to evaluate and improve retention; they also can continuously assess understanding through formative quizzes, promptings, and biometrics analysis.

- Educators can also use AI to generate authentic step-by-step tasks that assess student understanding. Students can use it with surprising ease to draft writing responses, brainstorm ideas, and create various audio-visual elements.

- AI could significantly assess higher-order cognitive skills, as categorized by Bloom’s taxonomy, specifically in the domains of applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

· For the “apply” level, AI creates customized quizzes and interactive simulations which challenge students to use learned concepts in new situations.

· In the “analyzing” domain, AI systems can evaluate student responses through complex problem-solving tasks, identify their ability to break down information into parts, and examine their construction of relationships or patterns.

· For “evaluating” student capabilities to make evaluations based on set criteria, AI-enabled platforms use natural language processing (NLP) to critique the quality of arguments and judgments in essays or reports.

· Finally, in the “creating” tier, AI can help assess student originality and innovation in project-based assignments by suggesting novel combinations of ideas or providing feedback on the creativity of solutions.

By integrating AI across these specific assessment methods, educators can precisely target and enhance the higher-level cognitive processes of applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating within the learning environment.

The Cons of Educative AI

While AI promises certain benefits for education, it also has significant issues concerning ethics, misinformation, bias, and transparency.

- AI systems can hallucinate information, that is, generate convincing, but completely fabricated output. This propagation of misinformation without sources or citations makes AI highly problematic as an instructional tool. AI models also frequently inherit and amplify societal biases due to their training data. Even AI designed without harmful intent can lead to prejudiced and problematic results. If students are unable to identify hallucinated misinformation or biased perspectives, such results can severely undermine the learning process as well as progress towards truthfulness, fairness, and social justice.

As the use of AI expands in education, more work is urgently needed to safeguard against these risks and mitigate damaging outcomes. The promise of AI is that it can assist student comprehension and retention; however, its potential ill effects, like unverified, erroneous, or biased information, raise deep concerns about its current limitations.

- Students may also become heavily dependent upon AI technology; specifically, they could use AI tools as shortcuts in doing and completing cognitive work as opposed to genuinely developing their own skills. More troubling is that even well-intentioned students could have their foundational remembering and understanding of concepts undermined by AI hallucinations, biases, and lack of proper sourcing. Students who apply, analyze, and evaluate such faulty knowledge in higher-order assessments without scaffolding and intervention from a professional teacher, can have their misconceptions reinforced.

In short, flawed AI-facilitated support of early comprehension and retention activities, as based on erroneous or biased information, would propagate inaccuracies within more advanced learning. So while AI offers some instructional benefits, it can backfire if foundational knowledge is corrupted early on by fabricated information, bias, or lack of transparency. Educators need to construct safeguards to ensure that reliance on AI as a teaching tool does not cement misunderstandings and thereby undermine the integrity of personalized education. The promise of instructional efficiency, as usual, circles back to the issue of teacher professionalism, content knowledge, and pedagogical planning.

- The interconnected nature of the internet and AI-powered tools can give students an inflated sense of easy access to all information. The hybrid digital learning medium often feels participatory and “magical”—with facts and concepts appearing to interlink seamlessly; the illusion for students is that any and all information is readily available without the deep work of recall and foundational comprehension.

Because the web and AI appear to stitch together a unified whole of instantly accessible knowledge, students may suffer from diminishing motivation to rigorously engage in proper understanding and retention. Here the phrase “surfing the web” takes on an unintended double meaning! If online information feels intuitively interconnected, students may erroneously believe that fruitful analysis, evaluation, and creation will also flow without their diligent engagement in the tasks of remembrance and comprehension. Teachers must ensure that students don’t get too caught up in surfing the waves of digital promise and instead make sure they put in the necessary cognitive work to arrive at the shore of solid knowledge acquisition!

- ELA and Social Studies learning standards demand that students build specialized skills rooted in logic, linearity, and focused critical thinking; acquisition of these skills requires that students analyze texts, construct coherent arguments, assess the credibility of sources, seek and consider diverse perspectives, and present claims backed by evidence. Social Studies, in particular, requires the additional practice of inquiry, evaluation, and civil discourse. Both fields demand that students build adult-level writing skills that can be applied in authentic contexts.

However, as I noted above, by using non-transparent, stitched-together AI information, students may become overly dependent on AI, compromising their advanced cognitive capabilities. Without teachers who intentionally scaffold research and reasoning within AI tools, students may lose their critical sharpness and linear thinking skills. AI efficiency cannot replace the targeted instruction that explicitly cultivates analysis, logical reasoning, reliable sourcing, argument construction, and the application of contextual knowledge. To guide students in developing these faculties, educators must thoughtfully blend the use of AI with rigorous learning standards via the traditional methods that require clear definitions and perspectives. This approach will preserve AI’s benefits while mitigating the risk of diminished advanced skills.

In view of these risks, it’s essential to reconsider the use of AI tools within learning. As students become immersed in AI platforms, which offer the same immediate gratification as other “cool” media like YouTube, gaming, and social media, the tension between those media and academic rigor will intensify. Educators must recognize that the “medium is the message” and work to deliberately counterbalance the cool media effects of internet and AI media by teaching their students analytical precision. Without building specialized analytical skills in ELA and Social Studies, students may fail to develop the capabilities vital to navigate and evaluate an AI-influenced informational world, where torrents of computer generated, unsourced, and potentially biased or erroneous information are deployed either unwittingly or as a source of propaganda. For those familiar, the worst-case scenario we should fear is an AI, cool-media version of “Plato’s Cave” (on steroids!).

Therefore, classrooms must become laboratories that intentionally cultivate higher level thinking skills, such as the ability to vet sources for credibility, reason logically, write coherently, and debate with evidence. The only way students can escape the deceptive allure of AI as a magical learning and information experience is through educators who teach students to use AI responsibly. Equipping students to accurately synthesize and produce knowledge is essential for real-world survival; the ability to actually find and evaluate evidence and sort what’s false from what’s true and then articulate it can mean not only success or failure on the job, but also determine the very health of civil society and democracy.

Process over product: rethinking educative assessment for AI

In the discussions about AI, many authors are concerned about how easy AI makes it to cheat. As an educator, I’m one of them. Although cheating is nothing new under the sun, educators and institutions should employ AI with deliberate care because AI does make it so easy to cheat, particularly on written and project-based assessments. With AI, the expectation that all students are writing their own essays or other assignments is—to say the least—problematic; that, in turn, makes the traditional practice of teachers grading assignments, when they’re likely composed by AI, time-wasting and, in fact, absurd. Detecting AI-generated content is challenging, if not impossible, and there is little to no educational value in students submitting work created by AI under the guise of their own effort. This practice not only bypasses the learning process but also undermines it.

However, the root of this issue may lie in educators who continue to rely on traditional methods of assessment, such as term papers and conventional forms of homework, in the AI world. These approaches anchor us to outdated concepts of how to validate knowledge and learning, leaving us ill-prepared to navigate the risks and benefits of generative AI technologies. Such largely unchanged traditional assessment methods—present in secondary education and even more prevalent in higher education—fail to capture the dynamic and evolving nature of knowledge in the digital era.

Educational theorist Grant Wiggins, in his book Educative Assessment (1998), advocated for authentic forms of assessment that move beyond the simple audit of student learning to instead truly measure a student’s ability to intelligently apply their knowledge. As he states, “the aim of assessment is primarily to educate and improve student performance, not merely to audit it.” For Wiggins, assessments that merely gather data on what students have memorized promote a view that assessment is “not germane to learning, and therefore best done expediently” (p. 7).

Wiggins calls instead for assessments anchored in “authentic work” (p.10)—tasks that “replicate the way in which a person’s knowledge and abilities are ‘tested’ in real-world situations” (p. 22). Authentic tasks require judgment, encourage exploration within an academic discipline, and push students to “do” the subject rather than just repeat what they have been taught. Students need transparency about assessment standards, multiple opportunities to practice complex tasks, and feedback that evaluates their performance against exemplary models (p. 14).

Though written twenty-six years ago, Wiggins’ insights highlight the risks of using AI tools in ways that undermine authentic assessment. Grading student-AI-generated essays does not measure a student’s writing and analytical abilities; it merely audits the student’s ability to use an algorithm. Similarly, it’s futile to assess students’ AI-created product without any intentional direction or feedback regarding the process and steps taken; what’s missed is whether students can authentically explore academic disciplines and apply knowledge judiciously. Pursuing efficiency and expediency over engagement with subject matter is precisely the concern Wiggins raises. Therefore, the responsible integration of AI into classrooms requires that educators carefully consider the purpose of their assignments and their assessment philosophy. As Wiggins asserts, the primary aim of assessment should be to educate and improve actual student performance.

Using AI-generated artifacts for assignments which are traditionally graded, however, will likely result in an audit. That doesn’t mean that genuine assessment is forever banished from AI-influenced classrooms. Maintaining transparency about expectations, giving students opportunities to practice the application of knowledge, and presenting and understanding examples of excellence are key recommendations from Wiggins that can guide educators in their assessments in AI-influenced classrooms. The purpose of education must remain the nourishment of student skills through engagement and exploration—with personalized feedback from the teacher—not the outsourcing of the learning process to algorithms.

What is needed are authentic assessments in which AI serves as a tool within a learning process marked by ongoing educator feedback and scaffolding towards student mastery. As Wiggins affirmed, it’s key that educators communicate transparent expectations along with multiple opportunities for students to demonstrate their skills. Instead of assigning a final product that can be AI-generated, educators must double down on the learning process itself. Concretely, this means that teachers must scaffold each step of an assessment while prioritizing authentic evaluation of student abilities. Teachers would benefit from protocols that leverage AI to check outputs against valid sources and interpretive rubrics while using human judgment to assess meaningful, student-centered and collaborative instructional activities. Every lesson then contributes towards building skills intentionally cultivated through formative assessments woven into classroom activities.

In this hybrid framework, AI operates as an assistive component of a broader assessment ecosystem guided by teachers. In the world of AI-assisted learning, over-reliance on direct instruction or summative tests, homework tasks, and essays is counter-productive. Traditional learning products must be balanced with collaborative learning activities and authentic formative assessments which capture enduring, synthetic understandings. Teachers can leverage generative AI technologies while retaining agency by using transparent expectations, multiple practice opportunities, and formative assessments that measure genuine comprehension—all key recommendations from Wiggins. This approach moves beyond outdated assessment mentalities while proactively shaping AI tools to supplement—not supplant—rich pedagogical environments where human educators nurture sophisticated, evaluative skills in students. The promise of AI lies in educators using it to strengthen what effective teachers already strive for: insightful, scaffolded and dynamic learning experiences that surpass the limited purpose of knowledge audits.

AI and the Liberal Arts

If educators approach AI mindfully, prioritizing authentic assessments that nurture genuine competencies, students can learn to navigate this technology responsibly. As I have shown, AI often presents as an enticingly participatory media experience, yet it relies on algorithms that generate probabilistically-generated and problematic content that lacks transparency. Users of this technology are obligated to supply accurate context to and analysis of content; doing so requires the application of specialized cognitive skills cultivated in the classroom. Like solving a math problem, if students cannot show their work in how they interpret and evaluate AI output, they lack foundational understanding.

The hybrid nature of AI-learning and its inevitable advances mean teachers must use every minute of their precious classroom time to scaffold the learning process with instructional activities and assessments that allow students to learn and practice identification of credible sources, logical analysis, and evidence-based reasoning and writing. Just as scientific hypotheses demand explanations of methods, AI-infused assignments should require students to display their interpretive and higher-order thinking skills, not just their final products. Students will then be equipped to contextualize AI’s useful but limited probabilistic outputs with specialized abilities for sustaining truth, accuracy, and transparency.

The promise of generative technologies lies in augmentation, not automation. Educators who adopt AI must reinforce activities and assessments that nurture sophisticated cognition, lifting learners beyond passive media absorption towards conscious transfers of learning. If AI is integrated thoughtfully as a tool that strengthens human teaching practices centered on mastery and growth-oriented feedback, students can develop the discernment and integrity increasingly vital for navigating an AI-influenced educational system where transparency and cognitive discipline cultivate ethical, creative, and responsible lifelong learners.

The advent of generative AI therefore calls educators to reaffirm the value of a comprehensive liberal arts education. As AI proliferates, both humanistic and quantitative disciplines become essential foundations for using new technology appropriately. The humanities teache methods of ethical analysis, critical evaluation of sources, philosophical questioning, and the cultivation of wisdom, all of which can contextualize the products of AI. Additionally, mathematical and scientific habits can equip students to audit algorithms logically, and empirically test outputs through evidence-based reasoning rooted in first principles of validity, causality, and truth-seeking. Students who receive broad training in the arts, humanities and sciences will acquire the discernment to ethically use, interpret and improve emerging AI technologies because they have been equipped with the necessary first principles of inquiry.

The central role of pedagogy in leveraging technology was recognized over two decades ago by Andee Rubin in her paper “Educational Technology: Support for Inquiry-Based Learning” (1998):

The answer to the question, “Will technology have a significant effect on K-12 education?” can only be answered by asking another question: “How is the technology used by students and teachers?” Their experiences are determined by the models of teaching and learning underlying classroom instruction. Pedagogy is the key.

Although Marshall McLuhan lived fifty years before the dawn of generative AI, his insights into the societal effects of electronic media offer a compelling framework for this vision of liberal arts education. McLuhan presciently foresaw that instantaneous networked information renders fragmented approaches obsolete, necessitating holistic interrelated learning that mirrors technology’s all-encompassing interconnectivity. Automation and AI are transforming our participation in knowledge retrieval and opening incredibly broad sources of data across all human sciences and cultures to the click of a GPT prompt and, in effect, have generated a something like a digital global nervous system. As we see in the polarization, emotion, and re-tribalization that has impacted civil discourse in the transfer of political and policy discussion to the cool media of Tiktok, Youtube, and other social media, in the same way broad liberal arts training is necessary if we are to critically navigate the entirety of content of human culture and knowledge as collectively mediated and experienced through the ever growing swarm of AI chatbots.

As McLuhan noted in Understanding Media (1964, p. 390),

Our education has long ago acquired the fragmentary and piecemeal character of mechanism. It is now under increasing pressure to acquire the depth and interrelation that are indispensable in the all-at-once world of electric organization. Paradoxically, automation makes liberal education mandatory.

In his view, the electric era had the effect of a sudden liberation of humanity from the mechanical routines of specialization. But he also knew that to realize this promise required “nomadic gatherers of knowledge” who are equipped for an “imaginative participation in society” through compass-setting education that fosters integral skills and discernment (1964, p. 391).

Francis Hittinger

© 2024