The thing, above all, that a teacher should endeavor to produce in his pupils, if democracy is to survive, is the kind of tolerance that springs from an endeavor to understand those who are different from ourselves. It is perhaps a natural human impulse to view with horror and disgust all manners and customs different from those to which we are used . . . And those who have never traveled either physically or mentally find it difficult to tolerate the queer ways and outlandish beliefs of other nations and other times, other sects and other political parties. This kind of ignorant intolerance is the antithesis of a civilized outlook . . . The educational system ought to be designed to correct it, but much too little is done in this direction at present. In every country nationalistic feeling is encouraged, and school children are taught, what they are only too ready to believe, that the inhabitants of other countries are morally and intellectually inferior to those of the country in which the school children happen to reside. Collective hysteria, the most mad and cruel of all human emotions, is encouraged instead of being discouraged, and the young are encouraged to believe what they hear frequently said rather than what there is some rational ground for believing.

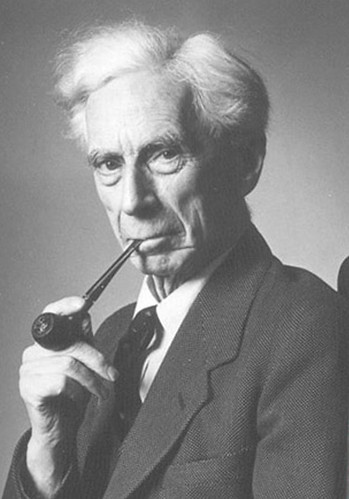

Bertrand Russell (1950, pp. 121-122)

This essay will become a chapter of my forthcoming book Liberal Education: Views from Antiquity to Modernity (tentatively titled)

- Education and Democracy

- The Current Situation

- Partisan Teaching is Ineffective

- Constitutional Law, Curricula and Academic Freedom

- The Apolitical Nature of Education

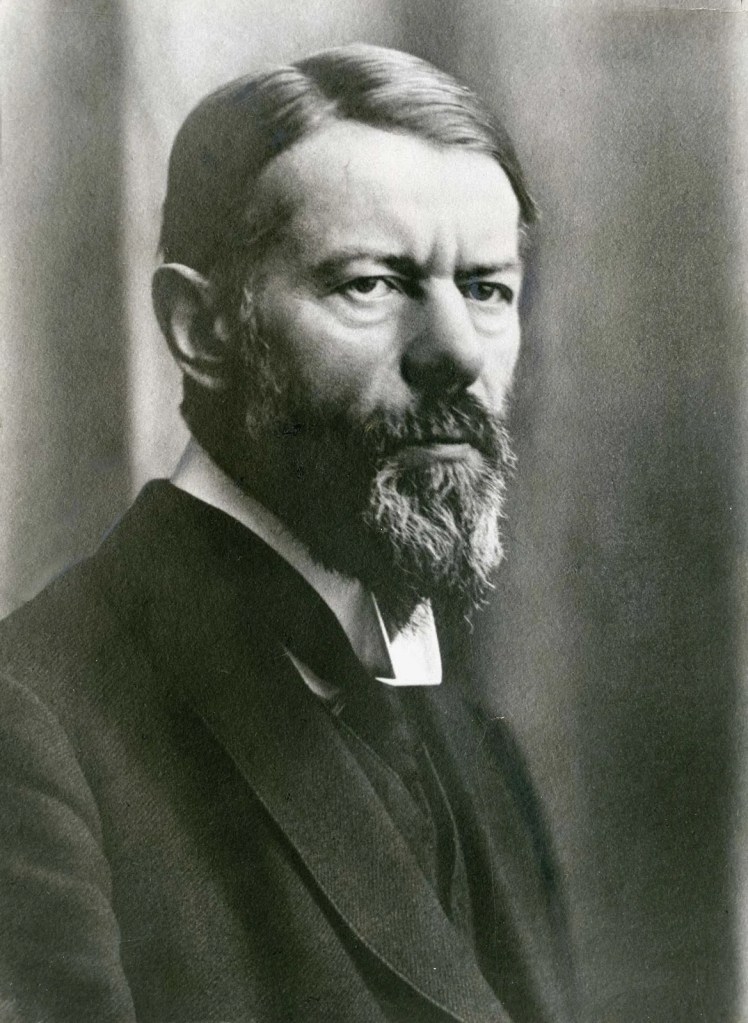

- Max Weber and the Non-Normative Nature of Science

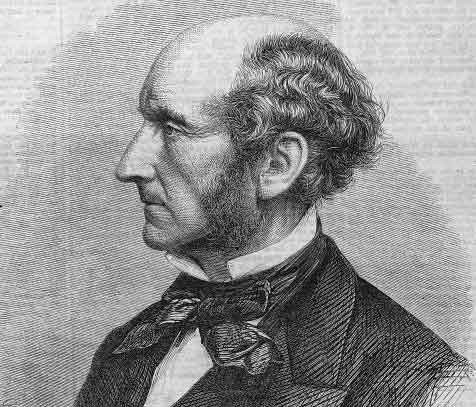

- John Stuart Mill: Liberty for Participatory Democracy

- Avoiding Social Tyranny

- Education and the Anti-Totalitarians: Arendt et al.

- Teachers as Protectors and Stewards

- Bertrand Russell and the “Good Teacher”

- Conclusion: Political Neutrality and Moral Purpose

Education and Democracy

Bertrand Russell’s poignant observation, written in the aftermath of the devastation of World War II, reminds us of the dangers of unchecked intolerance and the vital role of education in preserving democracy. The horrors of two world wars and the Holocaust, fueled by nationalistic fervors and the demonization of those perceived as “other,” underscore the disastrous consequences of failing to cultivate understanding and empathy across different cultures, beliefs, and ways of life. Russell underscores the perils of irrational ideas and the “collective hysteria” that flows from their uncritical acceptance by young people; educators should discourage rather than repeat what “they hear frequently said” and instead teach “what there is some rational ground for believing.”

Russell’s observations remain strikingly relevant in modern democracies, where political tribalism, high degrees of partisanship, and the decline of civil dialogue have been amplified by the 24-hour news cycle, social media, and culture wars. The digital age has accelerated and entrenched societal divisions, creating echo chambers that reinforce pre-existing beliefs and impede communication and understanding of different viewpoints. As individuals increasingly and uncritically accept opinions and political ideas that align with their in-group, the potential for finding common ground and engaging in constructive compromise diminishes. This ideological insulation undermines the value of cooperation and poses a grave threat to the functioning of democratic processes.

The Current Situation

In our present-day situation, Russell’s emphasis on the role of education in correcting ignorant intolerance and promoting understanding takes on renewed significance. The classroom serves as a crucial space where students can be exposed to diverse perspectives, learn to engage in fact-based, careful, and respect dialogue, and develop the critical thinking skills necessary to navigate the complexities of the modern world. By encouraging students to explore and understand viewpoints different from their own, educators can help bridge deepening divides and cultivate the kind of tolerance and empathy that is essential for the health and vitality of our democratic institutions.

The polarization affecting broader society, however, has already spilled over into the realms of education and research, challenging the traditional norms of academic discourse and learning environments in K-12 and higher education. Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff, in The Coddling of the American Mind (2018), argue that this climate has fostered an educational culture overly focused on protecting students from offensive ideas and discomfort. The authors suggest that such an approach can limit exposure to diverse viewpoints, leading to a form of intellectual homogeneity that mirrors the echo chambers seen in wider societal discourse while stifling intellectual growth and critical thinking skills. On the one hand, a lack of consideration of diverse views could harm the ability of future generations to navigate complex, divisive issues and engage in productive, respectful debate. On the other hand, the emphasis on avoiding discomfort at all costs in educational settings could further reinforce societal divisions, as students may be less prepared to encounter and critically assess ideas that challenge their preconceptions, a critical skill for negotiating and building consensus in any society, but especially in a polarized one.

The current environment is also harming the ability of teachers to model civil discourse and fair consideration of differing views in the classroom. High degrees of partisanship and the culture wars have made educators fearful that even unbiased discussions of difficult historical or social issues can trigger political passions or partisan responses. Over time, these factors may erode how willing educators are to present diverse perspectives within their communities because they fear backlash or misunderstanding. This kind of self-censorship not only diminishes the richness of the educational experience but also stifles the development of critical thinking and empathy among students. Instead of the classroom being a haven for academic progress, intellectual growth, and mutual respect, this environment can escalate conflicts and remake the classroom into a mirror of society’s polarized state. Moreover, the pressure to conform to or avoid certain viewpoints can create a sense of unease among teachers, undermining their job satisfaction and effectiveness, and substantiating the well-documented perception that teaching is not a respected career. However, state learning standards—backed by professional disciplinary standards in our social studies and language arts fields—require educators to approach difficult topics and train students how to develop interpretations and perspectives on diverse viewpoints. Doing this is an essential duty of educators.

In this essay, I argue that the classroom should serve as a training ground for democratic values, a space where students can practice critical inquiry, evidence-based reasoning, and respectful discourse. By examining Max Weber’s seminal text, Science as a Vocation (1919), I will explore the importance of separating personal political views from professional roles, particularly in teaching. Moreover, I will draw upon John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty (1859) to demonstrate why the free exchange of ideas is essential for the health and vitality of a democratic society. Finally, I will explore Bertrand Russell’s thoughts in The Function of a Teacher (1950) on the role the teacher must play in defending a free society, a role that gives the teacher more autonomy in promoting values within the classroom, but which is also rooted in the appreciation of tolerance and freedom. Ultimately, I argue that by fostering intellectual autonomy and civic competencies while respecting the teacher’s politically neutral role, educators can help prepare students to become informed and engaged participants in our civil society.

Partisan Teaching Is Ineffective

Let’s begin by considering the obvious reasons why politicized instruction in English/Language Arts and Social Studies classrooms is ineffective and detrimental to student learning and growth. As a Social Studies and Humanities teacher at both the high school and college levels, I have reflected extensively on this topic over many years.

First, partisanship only convinces those who already agree with you and, thus, is inappropriate in the classroom setting. Students grow up in households where family, friends, and parents hold political opinions that they likely view as authoritative, especially when students are so young that they have no other means of evaluating these views. Persuading students to change their beliefs through passionate classroom advocacy, no matter how assured the educator is that their view is the correct one, is akin to attempting to convert someone to a particular religion by knocking on their door: it is unlikely to succeed. It is also a misuse of the teacher’s position of authority. Just as a fervent denunciation of the Pope and presentation of an alternative religious viewpoint is unlikely to make a Catholic change their faith, similarly being a strong advocate for a particular party, candidate, or issue in the classroom will not convince students who hold different views. While a teacher can passionately present differing views with evidence and reasoning to contextualize their own opinions along with others, their primary educational goal should be to encourage students to form their own opinions based on the information provided.

Constitutional Law, Curricula and Academic Freedom

The role of the teacher in exploring partisan views, opinions, and controversial issues is further complicated by the limits American constitutional law draws around student speech, teacher speech, and state and local curricular jurisdictions. Regarding student speech, extensive case law, including Tinker vs. Des Moines (1969), has established broad protection for student speech in the classroom. Barring substantial disruption, the court held that students “do not shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” Although Tinker doesn’t explicitly address “hate speech,” it does provide a foundation for understanding when and how schools can regulate speech, something backed by many state anti-discrimination and hate speech statutes. For speech to be restricted, it must cause significant disruption to the school environment or infringe on the rights of others. This may include instances of hate speech and disruptive speech, as supported by decisions like Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser (1986) and Morse v. Frederick (2007).

Teachers have the academic freedom to deliver the curriculum within the boundaries set by their school boards’ policies and oversight, which are under the jurisdiction of state-adopted curricular standards. However, the Supreme Court and various appellate courts have consistently upheld the principle that school districts, not individual teachers, have the authority to define educational curricula. Teachers must adhere to the curriculum and policies set by their districts.

In Evans-Marshall v. Board of Education of Tipp City Exempted Village School District (2010), the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals clarified the limits of academic freedom for primary and secondary school teachers, stating, “Even to the extent academic freedom, as a constitutional rule, could somehow apply to primary and secondary schools, that does not insulate a teacher’s curricular and pedagogical choices from the school board’s oversight.” This case emphasized that while teachers have the freedom to educate, they must do so within the parameters set by their employing school district, and thus reinforced the district’s prerogative to determine what is taught and how.

Within the bounds of the approved curriculum, the academic value in subjects like history lies in helping students understand a variety of views and events, including those that are abhorrent, while also framing and articulating current controversial issues in a manner appropriate for both the age of the students and the school setting. In instances where inappropriate and non-academic speech arises, the teacher has a responsibility to firmly redirect the conversation and take a stand against such positions or re-contextualize them. Nevertheless, the instances in which a teacher has to restrict student views should be reasonably limited to truly hateful and disruptive speech, ensuring that the classroom fosters respectful modeling of democratic inquiry. The teacher’s primary role is to facilitate critical thinking and open-minded discussion, not to impose their own personal beliefs or restrict those of their students.

In addition to legal considerations, there are philosophical reasons why teachers should not forward partisan opinions. Such practice recalls the classical critique against sophistry, which emphasizes the potential distortion of education. Classical philosophers like Plato, in their examination of sophistry, highlighted the risk of prioritizing persuasive skill over the search for objective truth. They described sophists as adeptly using rhetoric to sway public opinion, often valuing persuasion above facts, evidence, and true reasoning. This method, they feared, could teach students that victory in argumentation, rather than the integrity of evidence and logical principles, constitutes truth. When education becomes a conduit for political agendas, it diverges from its primary role as a facilitator of independent inquiry and comprehensive understanding. Instead of encouraging students to explore ideas in their unadulterated form, it risks anchoring their learning experience to fluctuating partisan views, undermining the development of critical thinking skills and potentially biasing students’ perceptions and understanding of complex issues.

The Apolitical Nature of Education

School is presented, both academically and institutionally, as objective and apolitical. Students know this. From an early age, they learn that most academic subjects have methods for finding objectively right and wrong answers. By the time secondary students encounter complicated texts and views in English and social studies courses and are presented with methods for analyzing perspectives and arguments objectively, they should be well-versed in detecting value judgments and opinions. It is no surprise, therefore, that students clearly detect the partisan value judgments of their teachers when they are out of tune with academic standards and correct pedagogical practices.

Partisan pontification on controversial issues fails to fool students. Only those already in agreement continue to agree; others disengage. Students may perceive the extended pushing of a teacher’s opinion as indoctrination and shut down, while others will gravitate to teachers they believe share their “correct views.” Both outcomes are problematic. Instead, teachers should present facts, documents, and evidence. They should invite students to identify, classify, and analyze various views on issues themselves. Socratic discussions should be open-ended. The teacher’s role is to ask challenging questions and encourage students to justify their thinking.

In this vein, I used to tell my students I only care “that they think” not “what they think.” I remind them we are not in a totalitarian state like the USSR, which commonly used schools for political indoctrination. This is good. School should foster learning, growth, and critical thinking skills, not push political agendas.

Max Weber and the Non-Normative Nature of Science

In his essay “Science as a Vocation,” Max Weber discusses the status and significance of science (Wissenschaft) as practiced by professors dedicated to research and teaching in the university system. It is important to note that for Weber, the term science or “Wissenschaft” in German, denotes all the academic disciplines, including the “Geisteswissenshaften,” which we commonly refer to as the humanities and social sciences in anglophone university systems. Despite institutional differences between universities and secondary schools and historical changes since Weber’s era, his analysis of how and why politics infiltrated the classroom, from the perspective of the humanities and social sciences, is strikingly relevant.

In the second part of his essay, as he attempts to make the case for a clear separation between the respective vocations of politics and science, Weber argues that a fundamental problem with science as a vocation is its inability to address questions of its own meaning or provide guidance on how to live:

…What is the meaning of science as a vocation, now that the former illusions—the ‘way to true being,’ the ‘way to true art,’ the ‘way to true nature,’ the ‘way to true God,’ and the ‘way to true happiness’—have been dispelled? Tolstoy offers the simplest answer: ‘Science is meaningless because it does not answer our most crucial question: ‘What shall we do and how shall we live?’ That science fails to answer this is undisputed. The remaining question is how science gives ‘no’ answer, and whether it might still be useful to those who pose the question correctly (p. 9).

For Weber, even the ultimate value of scientific work—its “worth being known”—cannot be validated through the very means of science. He argues that such a value judgment “can only be interpreted in relation to its ultimate meaning, which we must either accept or reject based on our fundamental stance towards life” and not on the basis of the discipline. On the subject of the humanities and social sciences, Weber notes that while they give tools for interpretation, their limitations lie in their insufficiency for value judgements: “They enable us to understand and interpret political, artistic, literary, and social phenomena in terms of their origins. However, they do not tell us whether the existence of these cultural phenomena has been or is worthwhile. Nor do they address the further question of whether it is worth the effort to know them” (p. 10).

Weber’s point, from his perspective of a university social scientist, merits serious reflection, especially in our polarized era, which is marked by a lack of broad consensus on social and political values. Modern academic disciplines, through their methodologies, typically do not claim to provide answers on how we should live or what actions we ought to take. In philosophy, the distinction between normative (value and moral claims) and descriptive claims is helpful; while the humanities and social sciences are predominantly descriptive, they do offer students the chance to engage in normative judgments. Contemporary philosophy is rife with questions regarding the validity of normativity itself and supports the view that the question of value cannot be scientifically resolved but must be subjectively interpreted—a notion aligning with the biases of secular humanism. If the consequence of modern science is a form of “nihilism” or “perspectivism,” it is intriguing how it simultaneously dismisses its capacity for normative claims while becoming profoundly political in our contemporary academic institutions. And this is where Weber’s insight is so very interesting, because forwarding political opinions and value judgments in pedagogical contexts seems related to a paradoxical impulse to reclaim the sciences as a valid tool for ethical and political considerations—a reintroduction of this function into science, the validity of which science itself denies.

But this has not always been the case. Contrary to modern phenomenology, relativism, nihilism, or perspectivism, Aristotle posited in the Nicomachean Ethics (1141b) and elsewhere that ethics and the political sciences are practical, not theoretical, sciences from which humans can derive considerable normative insights through experience. While “Sophia” involves “nous” in the theory of the highest things, “phronesis” or practical wisdom involves deliberation and consideration from experience in things related to action in the human domain. Aristotle argues that political science and practical wisdom have the same “quality of mind” (ἔστι δὲ καὶ ἡ πολιτικὴ καὶ ἡ φρόνησις ἡ αὐτὴ μὲν ἕξις). In other words, Weber’s reflection on the ability of science, and in particular, the humanities, to answer moral and political questions, reflects a deep tension within the classical and medieval philosophical traditions, which have always conceived of their disciplines as not only capable, but necessary, means to make value judgments. Despite Socrates’ insistence in The Republic that he is merely ignorant about the meaning of justice (354c), the entire treatise is dedicated to examining the ways in which dialectical philosophy can develop both a proper epistemological method for morality and a normative vision of a good life and state. This approach contrasts with the contemporary mindset, where the political sphere, which has always been viewed as a domain of normative claims, faces logical contradictions in an age skeptical of normativity itself and lacking a political and ethical system. My reading of Weber’s view is that it is precisely because modern science is considered not able to resolve normative questions of value that it becomes a potentially dangerous vector of biased and partisan political engagement, reminiscent of the classical fears of sophistry, in a context where belief in normativity has waned.

Weber’s comments on teaching in “Science as a Vocation” offer valuable insights into the role of the educator and the importance of maintaining a clear distinction between the classroom and the public square in a liberal, modern age where ethical and political views are held to be primarily outside the bounds of science. Given the modern demarcation between political and ethical value judgments and the domain of science, Weber understood that introducing the latter into the former would result in inappropriate performative rhetoric about values. He argues that while disciplines like history, sociology, economics, and political science interpret the sciences, “politics is out of place in the lecture room,” whether on the part of students or teachers (p. 10). Weber states, “When speaking in a political meeting about democracy, one does not hide one’s personal standpoint . . . [to] take a stand is one’s damned duty” (p. 10). However, he emphasizes that such persuasive and deliberative rhetoric, often involving harsh words and political combat, is not a means of scientific analysis and that it “would be an outrage . . . to use words in this fashion in a lecture or in the lecture-room” (p. 10).

When addressing topics that veer into the political domain—a common occurrence in highly effective history and literature classrooms—Weber advises teachers to analyze the various forms and functions of political systems, compare them with non-democratic forms of political order, and help students find the point from which they can take a stand based on their ultimate ideals. However, he cautions, “The true teacher will beware of imposing from the platform any political position upon the student, whether it is expressed or suggested” (p. 10). Weber adds that “letting the facts speak for themselves” can be a backdoor for expressing one’s political views through emphasizing certain facts over others, something that should be avoided.

Weber’s conception of the teacher is that it is part of their duty as a scientist—knowing full well that science cannot prove matters of value, morality, and individual conscience—to abstain from political editorializing and politicizing the classroom. He states, “The prophet and the demagogue do not belong on the academic platform” (p. 11). This is not only because science cannot and should not direct instruction towards political opinion, but also because the classroom is fundamentally different from the deliberative and persuasive forum of the actual political town square. Weber writes, “In the lecture-room we stand opposite our audience, and it has to remain silent. I deem it irresponsible to exploit the circumstance that for the sake of their career the students have to attend a teacher’s course while there is nobody present to oppose him with criticism” (p. 11). Weber articulates a view similar to John Stuart Mill’s concept of liberalism, stating that a teacher devoted to the presupposition of science, which cannot prove statements of value on culture, politics, or ethics, can please neither a Freemason nor a Catholic, but will also offend neither. His advice is still relevant today; where partisan demands are so sharp, pleasing no one and offending no one are crucial. The teacher “must desire and must demand of himself to serve the one as well as the other by his knowledge and methods,” and the tenets of faith or prophecy are outside his purview.

In a true statement of principles central to a secular, liberal education, Weber declares,

‘inconvenient’ facts—I mean facts that are inconvenient for their party opinions. And for every party opinion there are facts that are extremely inconvenient, for my own opinion no less than for others. I believe the teacher accomplishes more than a mere intellectual task if he compels his audience to accustom itself to the existence of such facts. I would be so immodest as even to apply the expression ‘moral achievement,’ though perhaps this may sound too grandiose for something that should go without saying (p. 11).

In his analysis, Weber acknowledges that young people often crave a “leader” rather than a teacher, coming to schools and universities seeking more than mere analyses and statements of fact. This desire for political guidance, or even value affirmation, from educators is particularly relevant in our polarized age, where the lack of consensus on social and political values leaves many young people searching for direction and moral clarity. However, Weber firmly rejects this view as mistaken, asserting that “if he feels called upon to intervene in the struggles of world views and party opinions, he may do so outside, in the market place, in the press, in meetings, in associations, wherever he wishes. But after all, it is somewhat too convenient to demonstrate one’s courage in taking a stand where the audience and possible opponents are condemned to silence” (p. 13).

Weber’s insights shed light on the reasons behind the yearning among students for political leadership from educators in our divided times. As traditional sources of moral authority and shared values have eroded, young people increasingly look to teachers and professors to fill the void and provide guidance on contentious issues. However, Weber argues that the classroom is not the appropriate forum for such political proselytizing, as it exploits the power imbalance between teacher and student and undermines the primary purpose of education, which is to foster critical thinking and the pursuit of knowledge. By confining political activism to the public square, where ideas can be freely debated and challenged, Weber maintains that educators can better serve their students and uphold the integrity of their profession. His analysis serves as a timely reminder of the importance of distinguishing between education and indoctrination, especially in an era where the temptation to use the classroom as a platform for political advocacy is strong.

Weber ultimately argues that the task of the teacher must remain consistent with their vocation: contributing to the technology of controlling life by calculating external objects and human activities, providing methods of thinking and tools for thought, and helping students gain clarity. Regarding questions of value, “the teacher can confront you with the necessity of this choice. He cannot do more, so long as he wishes to remain a teacher and not to become a demagogue” (p. 14). If teachers succeed in this, Weber believes they stand in the service of “moral” forces, fulfilling the duty of bringing about self-clarification and a sense of responsibility. He concludes, “I believe he will be the more able to accomplish this, the more conscientiously he avoids the desire personally to impose upon or suggest to his audience his own stand” (p. 14).

John Stuart Mill: Liberty for Participatory Democracy

In contrast to Weber’s analysis, which rejects the idea that education has an explicit role in promoting ethical and political values, John Stuart Mill in On Liberty (1859) suggests that educators should at the very least forward the values that enable democracy to safeguard itself and avoid its own excesses through their practice. Mill asserts that free speech and the fair consideration of diverse viewpoints, through proper education, strengthen the participatory values of liberal democracies—the cornerstone of American society. For Mill, liberty properly understood is “liberty of conscience, in the most comprehensive sense; liberty of thought and feeling; absolute freedom of opinion and sentiment on all subjects, practical or speculative, scientific, moral, or theological . . . [and] liberty of expressing and publishing opinions.” Liberty thus understood is a sphere of the individual upon which society may only have an indirect interest and by which others may be affected “only with their free, voluntary, and undeceived consent and participation” (p. 22). However, in agreement with Weber, Mill’s insights imply that if teaching is practiced as a form of politics, value imposition, or demagoguery, and students are not trained in the academic practice of evaluation, comparison, and factual analysis, the classroom has failed them, because, in short, the educational experience has deprived them of their proper consent, assent, and ability to participate.

John Dewey, the famous American educational philosopher, pointed out in his work Democracy and Education (1916) that democracy is more than just a form of government; like Mill, he sees that it is also a participatory social system that is a form of common experience and associated living:

Since a democratic society repudiates the principle of external authority, it must find a substitute in voluntary disposition and interest; these can be created only by education. The extension in space of the number of individuals who participate in an interest so that each has to refer his own action to that of others, and to consider the action of others to give point and direction to his own, is equivalent to the breaking down of those barriers of class, race, and national territory which kept men from perceiving the full import of their activity (7.2).

Dewey asserts that education plays a crucial role in fostering the voluntary disposition and interest necessary for individuals to engage in the shared experience of democracy in a democratic society. Pursuant to Dewey’s insight, I argue that if the classroom remains unbiased and scientific on the educator’s part, it exemplifies the democratic and civic discourses of the respectful and non-harmful exchange of ideas that we cherish in our civil society. This exchange of ideas enables students, through the impartial examination of diverse perspectives, to formulate their own political and value propositions. They then are equipped to apply these skills outside the classroom in the realm of political persuasion and deliberation that our society requires. In this sphere, uniformity of thought is not the standard; multiple viewpoints and values must be negotiated and assessed based on facts and evidence, employing the fundamental principles acquired through a liberal education.

John Stuart Mill’s views on speech and the marketplace of ideas through education are therefore key to creating a classroom that supports democracy rather than one that harms it. By fostering an environment where students can freely express, examine, and challenge ideas, educators can help develop the critical thinking skills and open-mindedness necessary for effective participation in a democratic society.

In the first chapters of On Liberty, Mill frames his argument about free speech as a bulwark against the majority’s tendency to silence or mute their opponents. Mill alludes to The Republic where Plato presents his famous case of anacyclosis (the cyclical degradation of regimes), which describes the tendency of democracies to degrade into tyrannies, and presents his essay as one that advances the interests of “Civil, or Social Liberty.” He explains that the origin of liberal regimes was to check and limit sovereign powers from infringing upon the people’s liberties. However, over time, especially in the “continental section” of European liberalism, “what was now wanted was, that the rulers should be identified with the people; that their interest and will should be the interest and will of the people” (p. 5). The notion that the people have no need to limit their power over themselves might seem axiomatic when popular government was only a dream. However, according to Plato’s prediction in The Republic, the issue of the tyranny of the majority will emerge in liberal, democratic regimes, a fact known to political philosophers as diverse as J.S. Mill, Thomas Jefferson, and Machiavelli. As Mill puts it, “the will of the people . . . means the will of the most numerous or active part of the people . . . the ‘tyranny of the majority’ is now generally included among the evils against which society requires to be on its guard” (p. 7).

Avoiding Social Tyranny

The dangers inherent in the tyranny of the majority clearly connect to the concern for teachers to remain apolitical and for the classroom to be a “laboratory” of properly understood democracy. Mill’s apprehension, similar to that of de Tocqueville in Democracy in America (1835), is that democracies have a predilection for a “social tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression” (p. 8). He speaks of the “tyranny of prevailing opinion and feeling,” which attempts to impose its own ideas and practices and prevent the formation of any individuality “not in harmony with its ways,” by using its dominant standards of taste, morality, or propriety to stifle contrary opinions or conduct (p. 8). Mill’s well-known harm principle offers a partial defense against such tyranny, but his deeper argument suggests that a healthy civic culture of vigorous contestation of ideas is essential not only for preventing the suppression of minority views but also for maintaining the vitality of political truths themselves.

Mill’s argument is particularly relevant for the role of teachers in a democracy. He observes that “if all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind” (p. 30). It follows that when teachers present only one political viewpoint, they risk not only suppressing potentially true perspectives but also deny students the opportunity to fully understand the grounds of their own opinions. Mill contends that even erroneous views may contain valuable truths that can only be uncovered through earnest debate: “Though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of truth; and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions, that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied” (p. 98).

Mill warns of the dangers that biases in educational environments pose to the fabric of democratic societies; these biases can signal a process akin to ideological conformity even in the absence of overt suppression characteristic of authoritarian regimes. Such ideological conformity engenders a culture of self-censorship among dissenters, reminiscent of the grave outcomes in totalitarian states where intellectual repression has significantly marred generations of human potential. Mill asserts, “Our social intolerance kills no one, roots out no opinions, but induces men to disguise them, or to abstain from any active effort for their diffusion” (p. 59). The toll of this intellectual quiescence is profound and leads to “the sacrifice of the entire moral courage of the human mind” (p. 60).

Mill mourns the societal condition in which “a large portion of the most active and inquiring intellects find it advisable to keep the genuine principles and grounds of their convictions within their own breasts, and attempt, in what they address to the public, to fit as much as they can of their own conclusions to premises which they have internally renounced” (p. 60). Such an environment is incapable of fostering the emergence of open, fearless actors and logical, consistent intellects, characteristics that once defined the intellectual world. Instead, it yields individuals who are “either mere conformers to commonplace, or time-servers for truth, whose arguments on all great subjects are meant for their hearers, and are not those which have convinced themselves” (pp. 60-61).

Mill’s concern is that if diverse views are not allowed to be expressed and considered, the consequence is a “tyranny of opinion”:

In this age, the mere example of nonconformity, the mere refusal to bend the knee to custom, is itself a service. Precisely because the tyranny of opinion is such as to make eccentricity a reproach, it is desirable, in order to break through that tyranny, that people should be eccentric. Eccentricity has always abounded when and where strength of character has abounded; and the amount of eccentricity in a society has generally been proportional to the amount of genius, mental vigour, and moral courage which it contained (p. 126).

This insight holds profound implications for the modern American classroom and society as a whole. In an era where diversity, equity, and inclusion have become central themes in education and public discourse, it is essential to recognize that diversity encompasses a wide range of ideas, perspectives, and ways of thinking. A classroom that genuinely embraces diversity must not only tolerate but actively encourage and support eccentricity, independent thought, and nonconformity. By fostering an environment where students feel safe to express their unique views and challenge prevailing opinions, teachers can help cultivate the strength of character, mental vigor, and moral courage that Mill so highly valued.

Education and the Anti-Totalitarians: Arendt et al.

To these ends, Mill believes that a universal education, provided by a healthy blend of private and state schools, is necessary. However, he was leery of the dangers of the state monopolizing opinion. Therefore, he argues that examinations “should be confined to facts and positive science” and that “the examinations on religion, politics, or other disputed topics, should not turn on the truth or falsehood of opinions, but on the matter of fact that such and such an opinion is held, on such grounds, by such authors, or schools, or churches” (pp. 203-204). Mill asserts that “all attempts by the State to bias the conclusions of its citizens on disputed subjects, are evil; but it may very properly offer to ascertain and certify that a person possesses the knowledge, requisite to make his conclusions, on any given subject, worth attending to” (p. 204). In this assertion, Mill is foreshadowing the concerns of Arendt, Orwell, Huxley, Popper, and others, who warned against the dangers of totalitarianism, state propaganda, and the suppression of individual thought. These thinkers emphasized the importance of maintaining a pluralistic society where diverse opinions can be freely expressed and debated, as opposed to a society where the state dictates a single, dominant ideology.

The concerns of these thinkers are rooted in the belief that when the state monopolizes opinion and suppresses dissent, it leads to the erosion of critical thinking, the capacity for independent thought, and individual liberty.

Hannah Arendt, in her work The Origins of Totalitarianism (1973, p. 468) demonstrated how the state’s control over education and the dissemination of information can lead to the formation of a conformist society where individuals are unable to think for themselves, observing that “the aim of totalitarian education has never been to instill convictions but to destroy the capacity to form any.” Similarly, George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984 (1949) depicts a society where the state’s control over language and information leads to the suppression of individual thought and the creation of a single, dominant narrative.

Likewise, Mustapha Mond, the antagonist political “controller” of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), embodies a society where the state’s control over education and conditioning leads to the formation of a conformist population. Ideas contrary to what the state holds are “not to be published” lest

unsettled minds among the higher caste . . . lose their faith in happiness as the Sovereign Good and take to believing, instead, that the goal was somewhere beyond, somewhere outside the present human sphere, that the purpose of life was not the maintenance of well-being, but some intensification and refining of consciousness, some enlargement of knowledge (p. 180).

Karl Popper, in his Open Society and its Enemies (1956), advocated for a balance of liberalism and state intervention in education (p. 106), but also extensively warned of the dangers of totalitarianism in this regard, especially of the potential of education to serve totalitarian ends and official state ideologies. Popper famously critiques Plato’s classic proposal for the education of the ruling class—which would ban religious myth, poetry, and tragedies (as in Huxley’s modern dystopia) in order to create a perfectly just state in the Republic—as a program whose “educational aim is not the awakening of self-criticism and of critical thought in general” but of “indoctrination” and “ the strictest censorship” (p. 125).

Teachers as Protectors and Stewards

These various perspectives suggest that a pedagogy aimed at preparing students for democratic citizenship must go beyond the mere imparting of political dogmas and instead cultivate students’ capacity for critical reflection. As Mill warns, “The fatal tendency of mankind to leave off thinking about a thing when it is no longer doubtful, is the cause of half their errors” (p. 80). By having students actively debate political ideas from contrary perspectives, teachers can ensure a more vital and enduring understanding of political principles while guarding against the calcification of ideas into unquestioned dogma. This process also serves as a pedagogical safeguard against the danger of democracies slipping into totalitarian regimes which then use the educational system as part of their system of repression.

Mill’s defense of the liberty of thought and discussion offers a compelling pedagogical rationale for Max Weber’s insistence that teachers must refrain from political advocacy in the classroom; by not acting as advocates, teachers become protectors and stewards of the examination of diverse voices and perspectives. By maintaining political neutrality and promoting the vigorous contestation of ideas, teachers can create a “laboratory” of democracy in which students develop the habits of critical thinking essential for anti-totalitarianism and democratic citizenship. This approach not only aligns with the principles of a liberal education but also prepares students to engage in the political discourse and deliberation that our society demands, where multiple viewpoints and values must be negotiated and evaluated based on facts, evidence, and the critical thinking skills acquired through education.

Bertrand Russell and the “Good Teacher”

In his thought-provoking essay “The Functions of a Teacher” from Unpopular Essays (1950), Bertrand Russell eloquently articulates the vital role teachers play in shaping the minds and characters of their students, and by extension, the future of society. While Russell shares many views with Weber and Mill, as previously discussed, he places greater emphasis on the teacher’s autonomy to impart free thinking as a prophylactic against the concerns of anti-totalitarian thinkers. However, Russell firmly believes that education should not be a vehicle for political indoctrination, even if it needs to support democracy and tolerance, a view that aligns him with Weber’s fundamental principles. In contrast to Weber’s view that science cannot answer moral questions, however, Russell maintains that rational inquiry and scientific methods can indeed shed light on ethical concerns.

Russell illustrates this point by highlighting the dangers of educational systems that prioritize the instillation of official dogmas over the development of critical thinking skills. He writes,

so long as [the teacher] is teaching only the alphabet and the multiplication table, as to which no controversies arise, official dogmas do not necessarily warp his instruction; but even while he is teaching these elements he is expected, in totalitarian countries, not to employ the methods which he thinks most likely to achieve the scholastic result, but to instill fear, subservience, and blind obedience by demanding unquestioned submission to his authority (p. 114).

Russell argues that the totalitarian approach to education, which stifles free discussion and promotes fanatical bigotry, is particularly destructive when combined with nationalist ideologies that deny the existence of a common international culture. He observes that in countries such as Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, the young were indoctrinated with a narrow, nationalistic worldview that left them ignorant of the world outside their own country and incapable of engaging in open dialogue with those who held different opinions.

It is crucial to understand that Russell’s perspective, which grants teachers more leeway than Weber’s, developed in the aftermath of two devastating world wars and the terrible destructiveness of authoritarian and totalitarian ideologies which also influenced Ardent’s and Popper’s views. Having witnessed the horrific consequences of unchecked authoritarianism and the suppression of free thought, Russell’s writings were deeply influenced by the urgent need to safeguard intellectual freedom and prevent the rise of oppressive regimes.

Within this historical context, Russell argues that the primary duty of the teacher is not merely to impart knowledge: ‘if democracy is to survive,” the teacher must produce in his pupils “the kind of tolerance that springs from an endeavour to understand those who are different from ourselves” (p. 121). Russell cautions against the perils of prevailing dogmatism in education, which leads to censorship and repression: “Dogmatists the world over believe that although the truth is known to them, others will be led into false beliefs provided they are allowed to hear the arguments on both sides” (p. 116). This view, according to Russell, results in one of two unfortunate outcomes. Either a single group of dogmatists dominates and suppresses new ideas, or competing dogmatists control different regions and promote hatred against each other. The former stifles progress, while the latter threatens to destroy civilization entirely. Russell asserts that teachers should serve as the primary defense against both of these dangers.

Russell’s words serve as a powerful reminder of the dangers we face when education becomes subservient to the demands of the state, the prevailing orthodoxy of partisan groups, or the tyranny of the majority within a democracy, let alone a totalitarian state. He cautions that when teachers are “dominated and fettered by an outside authority,” they lose the ability to inspire their students and guide them towards a more enlightened understanding of the world. Furthermore, when education is influenced by partisan bias or political agendas, it can stifle free expression, suppress dissenting opinions, and undermine the pursuit of scientific truth.

In a passage that resonates strongly with the central themes of this essay, Russell writes, “If the world is not to lose the benefit to be derived from its best minds, it will have to find some method of allowing them scope and liberty in spite of organization. This involves a deliberate restraint on the part of those who have power, and a conscious realization that there are men to whom free scope must be afforded” (p. 123). Intellectual freedom and pedagogical judgment is essential for teachers who must advance human knowledge and understanding, even in the face of institutional constraints or societal pressures.

The role of educators as articulated by Russell underscores society’s immense responsibility in safeguarding the intellectual freedom of educators. By granting teachers the autonomy to exercise their professional judgment and expertise, we create the conditions necessary for them to inspire and guide the next generation of thinkers and leaders. However, as Weber argues, this autonomy also comes with a responsibility on the part of educators to restrain their impulse to express personal opinions or engage in activism within the scope of their instruction. Teachers must recognize the importance of maintaining a clear distinction between their role as educators and their personal political beliefs if they are to ensure that their classroom remains a space for open inquiry and the free exchange of ideas. This balance between academic freedom and professional responsibility is essential for fostering an educational environment that encourages critical thinking, intellectual curiosity, and the pursuit of knowledge. At the same time, as Russell points out, this professional autonomy must be imbued with a deep sense of moral purpose and what we could call a love of humanity. Russell’s vision, as articulated in his essay, is that the ultimate aim of education is not merely to produce skilled workers or obedient citizens, but to cultivate fully realized human beings who possess a keen understanding of the world and their place within it—without distortions. Education, therefore, is an act of moral civilization-building, where knowledge aims to emphasize understanding and peace rather than ignorance and conflict. “The civilized man,” he writes,

where he cannot admire, will aim rather at understanding than at reprobating. He will seek rather to discover and remove the impersonal causes of evil than to hate the men who are in its grip. All this should be in the mind and heart of the teacher, and if it is in his mind and heart he will convey it in his teaching to the young who are in his care (p. 118).

In Russell’s understanding, no one can be a good teacher unless they have both feelings of warm affection towards their pupils, and a genuine desire to impart to them what they themselves believe to be the value of education in service of the human good. This understanding is in stark contrast to the attitude of the propagandist, who sees pupils as potential soldiers in an army, serving purposes that lie outside their own lives and ministering to unjust privilege or despotic power. The propagandist, Russell argues, thwarts the natural growth of students, destroying their generous vigor and replacing it with envy, destructiveness, and cruelty. But a teacher who respects his or her students and has their best interests, and those of humanity in mind, will

. . . stand outside the strife of parties and endeavour to instill into the young the habit of impartial inquiry, leading them to judge issues on their merits and to be on their guard against accepting ex parte statements at their face value. The teacher should not be expected to flatter the prejudices either of the mob or of officials. His professional virtue should consist in a readiness to do justice to all sides, and in an endeavour to rise above controversy into a region of dispassionate scientific investigation. If there are people to whom the results of his investigation are inconvenient, he should be protected against their resentment, unless it can be shown that he has lent himself to dishonest propaganda by the dissemination of demonstrable untruths (p. 116).

Educators, while exercising restraint in expressing their personal opinions, must still strive to foster this sense of shared humanity and respect for diversity within their students. By doing so, they fulfill their moral obligation to shape not only knowledgeable individuals but also empathetic and open-minded citizens who are prepared to navigate the complexities of a pluralistic society.

Conclusion: Political Neutrality and Moral Purpose

In light of the insights provided by Mill, Weber, and Russell, it is evident that teachers should strive for political neutrality in their instruction while maintaining a deep commitment to fostering critical thinking, open-mindedness, and a shared sense of humanity among their students. This approach not only aligns with the principles of a liberal education but also serves as a bulwark against the dangers of dogmatism, ideological conformity, and the erosion of democratic values.

As Weber argues, teachers must refrain from imposing their personal political views on students, recognizing that the classroom is not an appropriate forum for partisan advocacy. By maintaining political neutrality, educators can create a space where students can express their own opinions, engage in respectful dialogue, and develop their capacity for independent thought. This neutrality aligns with Mill’s emphasis on the importance of subjecting all ideas to rigorous debate and scrutiny, which is essential for the pursuit of truth and the prevention of ideological tyranny.

However, as Russell points out, political neutrality does not mean a lack of moral purpose or a disregard of the broader aims of education. As we navigate the challenges of an increasingly complex and divided world, we must heed the wisdom of thinkers like Mill, Weber and Russell, and accept our responsibility to cultivate in our students a deep understanding and acceptance of our diverse and shared human experience. In addition, by maintaining political neutrality, we can impart the key concepts, skills, and knowledge of our social studies and English/language arts curricula, thereby equipping students with the tools they need to become informed, engaged citizens. By modeling and encouraging students to approach complex issues with empathy, open-mindedness, and a willingness to engage in good-faith dialogue, educators can foster the tolerance and understanding essential for a more enlightened, humane, and democratic society in a century whose ultimate political alignments are in danger of totalitarians and authoritarianism.

© Francis Hittinger 2024

All Rights Reserved